Six Things We Learned About Our Changing Climate in 2013

SMITHSONIAN.COM’s Special Report: Energy Innovation – published Dec. 27, 2013

2013 was a great year for science. We discovered hundreds of exoplanets, found yet more evidence of ancient water on Mars and learned all about our species’ own evolution.

But it’s important to remember that, in terms of the long-term survival of both our species and all others on the planet, 2013 is remarkable for a much darker reason. It’s a year in which we’ve pushed the climate further than ever away from its natural state, learned more than ever about the dire consequences of doing so, and done as little as ever to stop it.

As greenhouse gas emissions soar unabated and the ramifications become rapidly apparent, here’s a rundown of what we learned about climate change in 2013:

1. There are record levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Starting in 1958, scientists at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii have tracked the general concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, far from power plant smokestacks or carbon-emitting traffic. This past May, for the first time in human history, they saw carbon dioxide levels surpass 400 parts per million (ppm).

The planet hasn’t seen carbon dioxide concentrations this high anytime in the past million years—and perhaps anytime in the past 25 million—but what’s truly alarming is how rapidly they’re rising. Pre-industrial levels were likely around 280 ppm, and the first measurements at Mauna Loa were 316 ppm. Now that we’re emitting the gas faster than ever, it’s not a stretch to imagine that people alive today could, as the Carbon Brief predicts, “look back on 400 ppm as a fond memory.”

2. Global warming may have appeared to slow down, but it’s an illusion. Over the past few years, average land surface temperatures have increased more slowly than in the past—prompting climate change deniers to seize upon this data as evidence that climate change is a hoax. But climate scientists agree that there are a number of explanations for the apparent slowdown.

For one, there’s the fact that the vast majority of the world’s warming—more than 90 percent—gets absorbed into the oceans, and thus isn’t reflected in land temperatures, but is reflected in rising sea levels and ocean acidification. Additionally, even during a period in which average land temperatures continue to climb, climate models still predict variability for a variety of reasons (like, for instance, the El Niño/La Niña cycle).

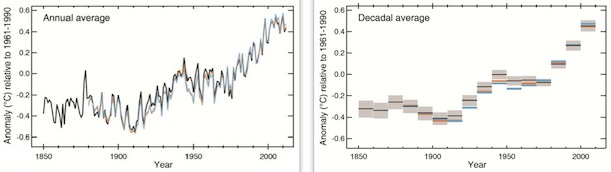

Click to enlarge. Image via IPCC AR5 Report

But all this variability merely masks a consistent underlying trend. Break down the graph at left (which shows annual temperature changes) into decade averages, shown at right, and the overall picture becomes clear. As physicist Richard Muller aptly described it in a recent New York Times op-ed, “When walking up stairs in a tall building, it is a mistake to interpret a landing as the end of the climb.”

3. An overwhelming majority of scientists agree that human activities are changing the climate. Healthy disagreement is a key element of any science—a mechanism that drives the search for new and ever-more-accurate hypotheses. But human-driven climate change, it turns out, is a particularly well-established and broadly-accepted idea.

A recent survey of every scientific study published between 1991 and 2012 that included either the phrase “global climate change” or “global warming” underscored this point. In total, of the 11,944 studies the researchers found, 97.1 percent supported the idea that humans are changing the climate, and when the authors of these studies were contacted by the researchers, 97.2 percent of them explicitly endorsed the idea.

The initial phase of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fifth Report, published in September, further emphasized this consensus. The report, a synthesis of the research conducted by thousands of climate scientists around the planet, found that it’s “extremely likely” that human activities are the driving force behind the changing climate.

4. Climate change is already impacting your life. It’s tempting to think of climate change as a far off problem that we’ll have to deal with eventually. But an abundance of studies released this year show that the consequences of climate change are already being felt in a huge variety of ways, from the everyday to the catastrophic.

In terms of the former, Climate change is forcing insurance companies to raise their premiums, driving up the price of coffee, altering the taste of apples, helping invasive species take over local ecosystems, threatening the suitability of wine-growing regions, reducing our ability to perform manual labor, melting outdoor ice hockey rinks and causing plants to flower earlier.

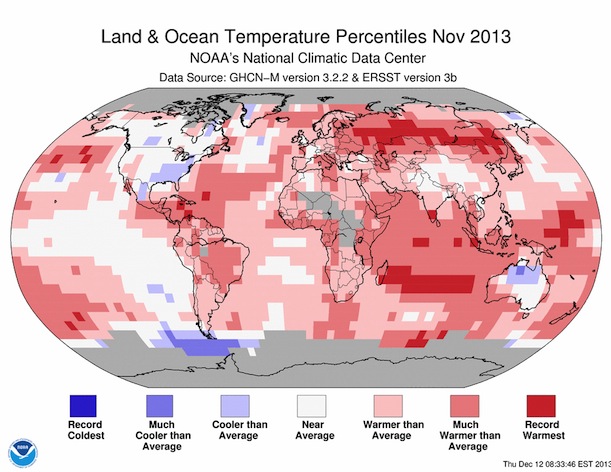

And, of course, there’s the most direct consequence: warming. Globally, we observed the hottest November on record, part of a string of 345 straight months with above-average temperatures compared to the 20th century average.

A map of temperatures recorded around the world during November, the hottest November on record. Image via NOAA

But it’s the catastrophic ramifications of climate change that are most terrifying. An altered climate will mean more extreme weather as a whole, something we’ve already begun to see all around the world. India, for instance, has experienced a wildly unpredictable rainy season recently, with some years bringing disastrously weak monsoons, but this year’s was unprecedentedly heavy, with many areas receiving record 24-hour rainfalls and three times as much rain in total as average, leading to flooding that caused more than 5,700 deaths.

Meanwhile, the strongest typhoon ever to make landfall—with winds exceeding 190 miles per hour—hit the Philippines, killing at least 6,109 people. While it’s impossible to link that one specific event to climate change, scientists agree that climate chage will make particularly intense storms more common. Elsewhere, in 2013 we sawBrazil’s worst drought ever, Australia’s hottest summer on record, all-time heat records set in Austria and Shanghai, and what even the National Weather Service called a “biblical” flood in Colorado.

5. There’s not nearly enough being done to stop climate change. There have been some bright spots in 2013: Production of renewable energy in the U.S. has continued to increase, now accounting for a little over 14 percent of the country’s net energy generation. Due to this trend—and the continued decline of coal, replaced in part by less carbon-dense natural gas—U.S. carbon dioxide emissions are at the lowest levels they’ve been in twenty years.

But this apparent good news simply hides another troubling trend: Instead of burning our coal, we’re simply exporting more and more of it abroad, especially to China. And unfortunately, there are no borders in the atmosphere. The climate’s going to change no matter where fossil fuels are burned.

This further emphasizes the need for an international agreement to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, something negotiators have repeatedly tried and failed to reach before. Climate activists are hopeful that the 2015 round of UN negotiations, to be held in France, will result in a meaningful agreement, but there are a lot of hurdles to be cleared before that can happen.

6. There is one key formula to preventing catastrophic climate change. The amount of data and fine detail involved in calculating climate change projections can seem overwhelming, but a report released this summer by the International Energy Authority articulates the basic math.

Of all existing fossil fuel reserves that are still in the Earth—all of the coal, oil and natural gas—we must ultimately leave two-thirds unburned, in the ground, to avoid warming the climate more than 2° Celsius (3.6° Fahrenheit), a number scientists recognize as a target for avoiding catastrophic climate change.

If we can figure out a way to stay within this carbon budget before it’s too late, we can still avert a climate disaster. If we can’t, then we too might look back at today’s record-breaking temperatures, droughts and floods as a fond memory of milder times.

Image via NASA